The symptom scan is one of the most useful tools I have found to deal with anxiety attacks. It takes this perception of an anxiety attack as one big wave of doom sweeping over us, and breaks it down into its component parts. The technique is very simple: scan through your body, noticing each symptom, where it is and how it feels, and then describing it to yourself. For example: “very tense abdominal muscles, buzzing sensation in tummy area, rapidly pounding heart, tight feeling in throat, dizzy feeling in head”. It’s important to actually describe your observations very specifically in words to yourself. By breaking the overall anxiety attack down into smaller, distinct sensations, our perception of it can change from a single “wave of doom” to a collection of uncomfortable physical sensations in the body. It also helps move our perception of the attack away from being mainly inside our head, out into the various parts of the body.

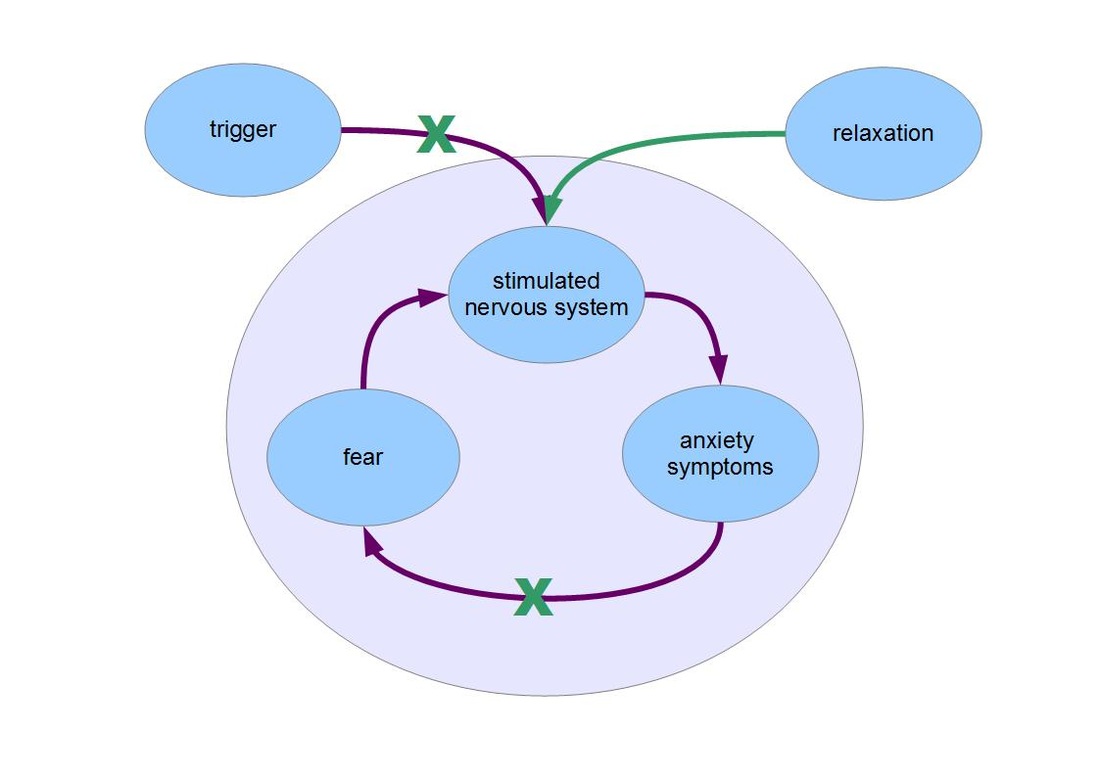

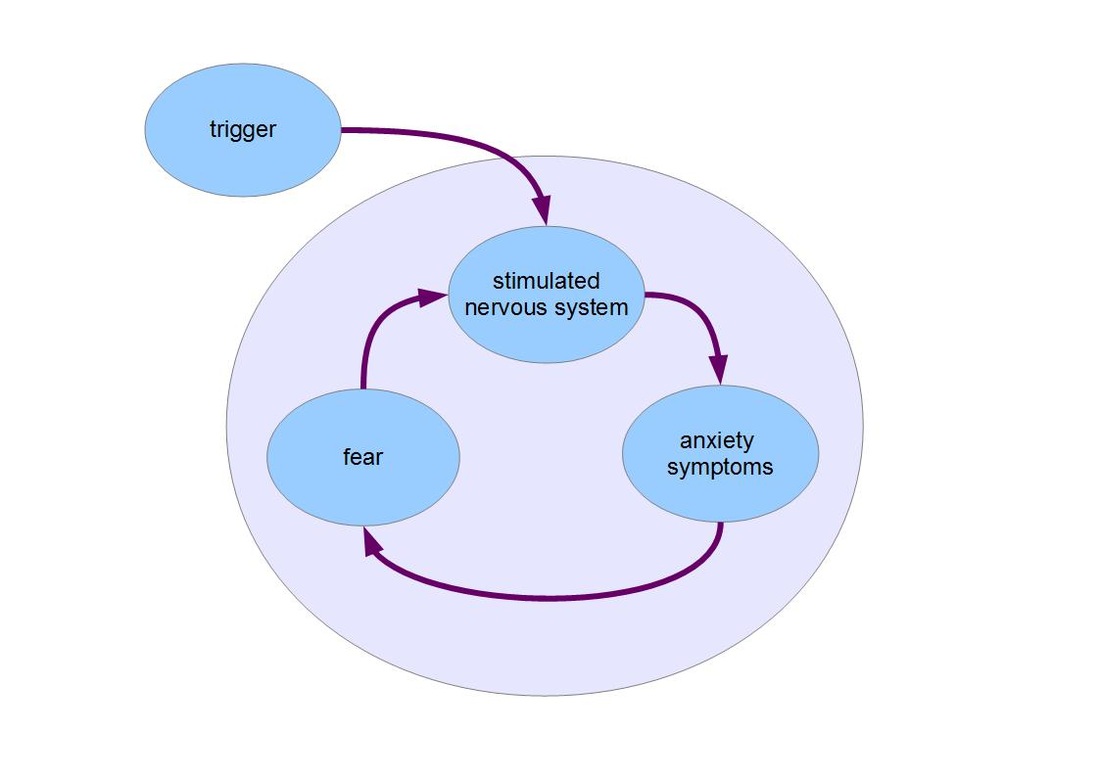

Remember that our brain may interpret the physical fear response as emotional fear. We can learn to reinterpret our fear response as just a collection of uncomfortable physical sensations. In fact, we can even use these kinds of terms in our self-talk to reassure ourselves and convince our brain that we really are safe and there is nothing to fear. The pounding heart is just from adrenaline making our heart beat harder and faster. It’s just a physical symptom producing an uncomfortable sensation. When we reinterpret what we are feeling in this new way, the “wave of doom” goes away. By reducing our emotional fear, the intensity of the fear response may be reduced, because we are no longer feeding the anxiety cycle with more fear. Sometimes, just practising this technique is enough to stop an anxiety attack completely.

One of the difficulties in learning this technique is that you have to go “into” the sensations, when our natural instinct is to avoid and resist them. By having the courage to really feel the symptoms, we can learn to be more accepting of them. We also become better at observing what is really going on in the body, rather than being overwhelmed by the perceptions and interpretations our mind puts on the situation.

So the symptom scan technique can have two benefits. Firstly, by reducing our interpretation of the anxiety attack as “fear”, we stop feeding the anxiety cycle, and so the intensity of the anxiety attack may be reduced. Secondly, even if anxiety symptoms persist, by reinterpreting the symptoms as not fear but simply a collection of uncomfortable physical sensations, they becomes easier to accept and more tolerable. The more you practise this technique, the easier it will get, and the quicker you’ll be able to feel these benefits.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed